By Joey Clarke, Senior Science Communicator

While the impact of big rainfall and flood events can be disastrous for human populations, the effects on wildlife are varied. At a broad landscape scale, northern Australia’s ecosystems have evolved under a regime of long, rainless dry seasons and intense wet seasons. Each wet season brings a flush of new growth, creeks and wetlands are replenished and the brown savanna grasslands turn green. The surge of vegetation growth is a major driver of productivity in these ecosystems: it triggers a proliferation of invertebrate life, while plants produce flowers, fruit, and seeds which nourish a diversity of larger animals – amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds. For many groups of animals, the wet season is a time of abundance and a trigger for breeding activity.

Brad Leue/AWC

Brad Leue/AWC

Immediate effects

As you might expect, flooding poses an immediate threat to some animal species. For birds like the Purple-crowned Fairywren, the wet season is when most breeding activity takes place. The fairywrens build their nests in the thick stands of Pandanus that line watercourses like Annie Creek, usually just a few metres above the water level. In previous years, the research team from Monash University who have been studying this population has documented nests being destroyed by floods, with an immediate impact on recruitment of young birds to the population. Larger and more mobile species like wallabies are usually able to seek refuge on higher ground. Snakes and goannas are frequently observed swimming to and climbing into branches or sticks to seek refuge from rising floodwaters.

Longer-term effects

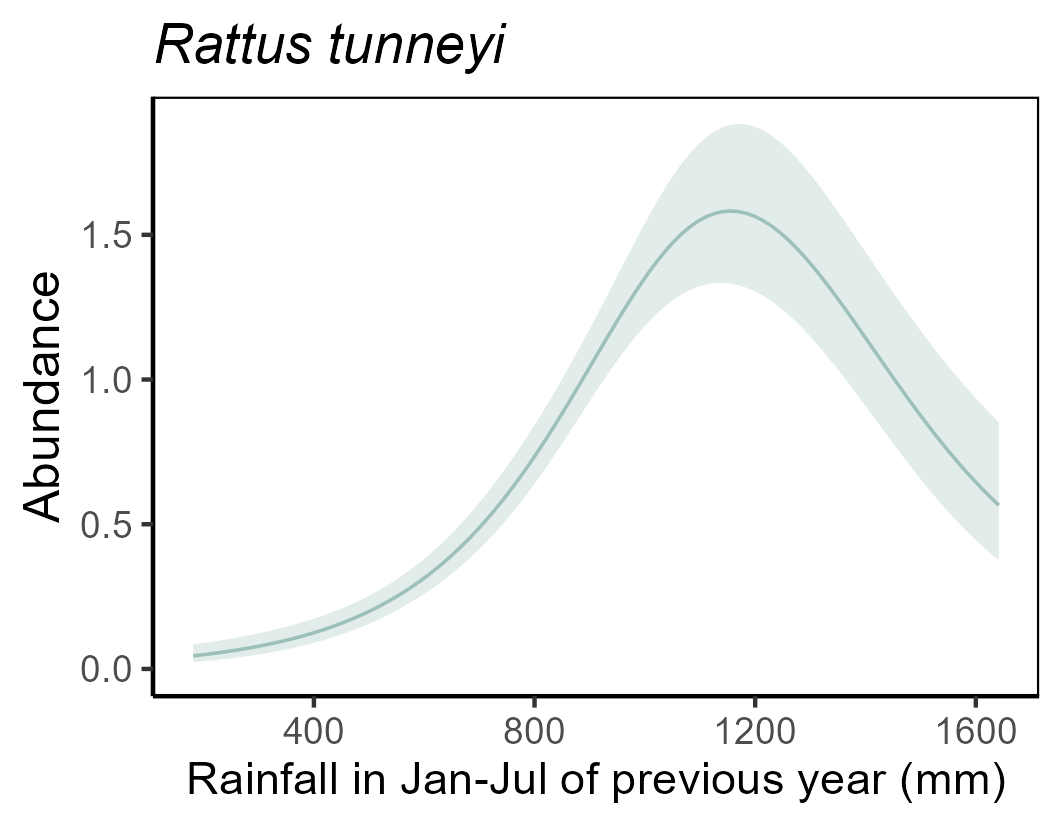

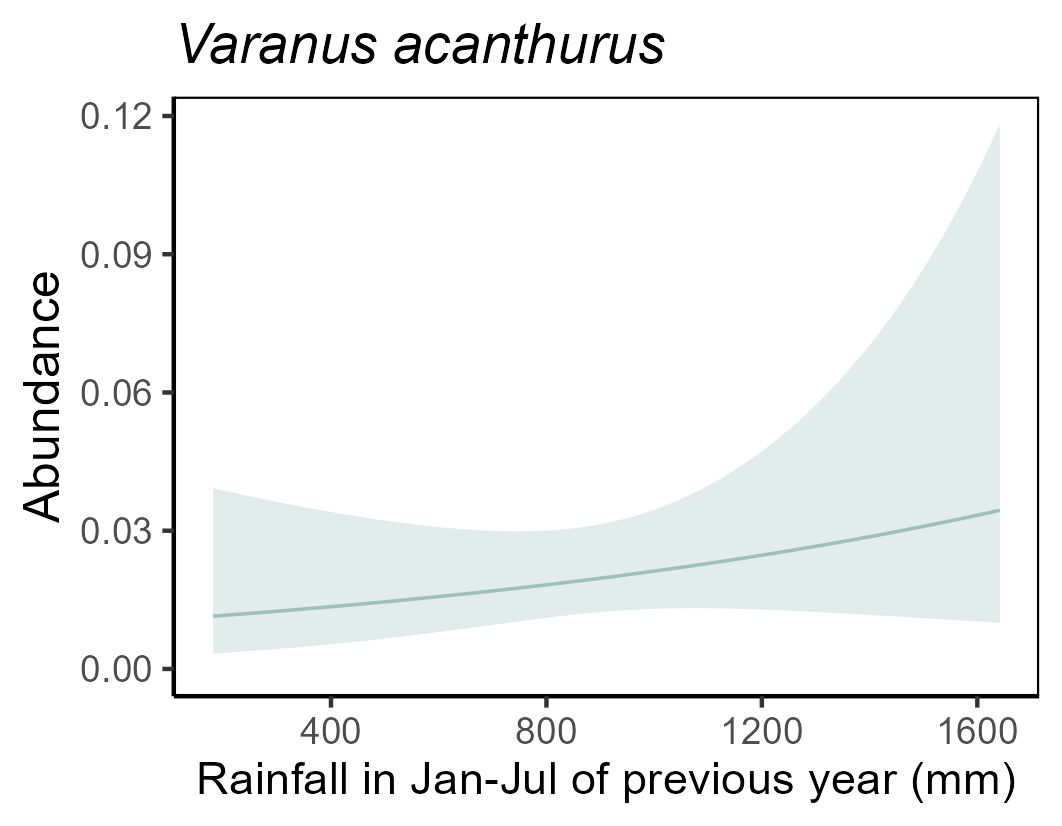

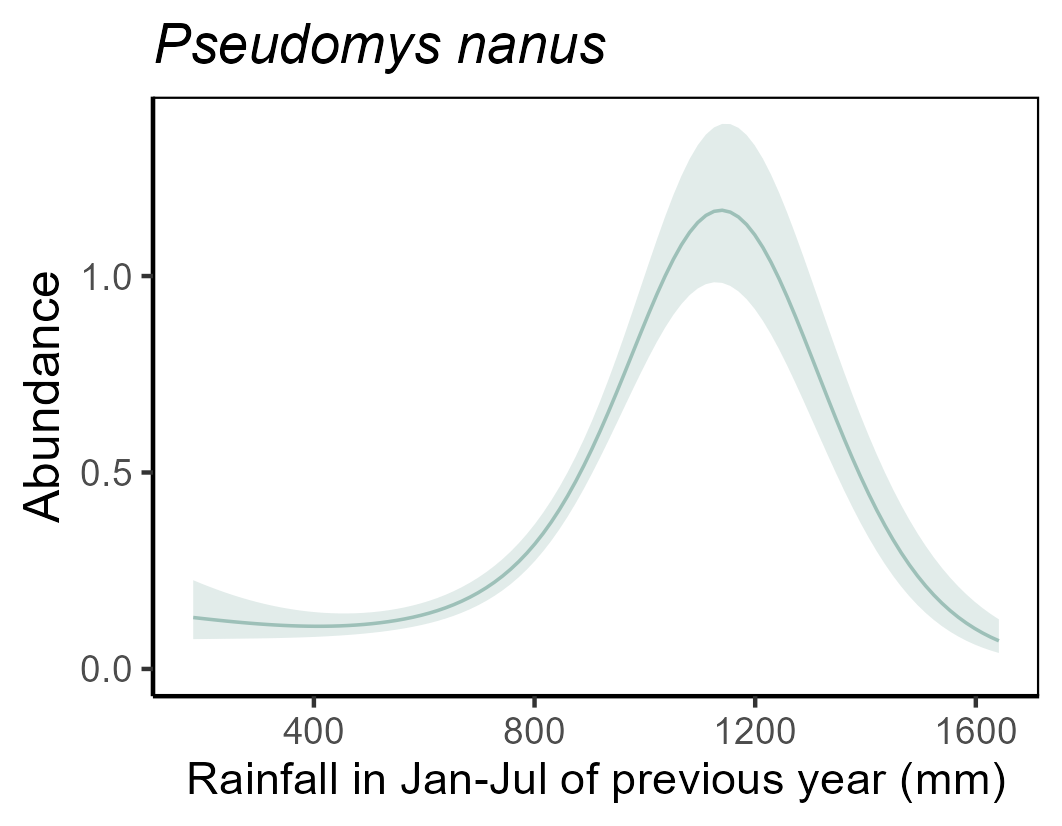

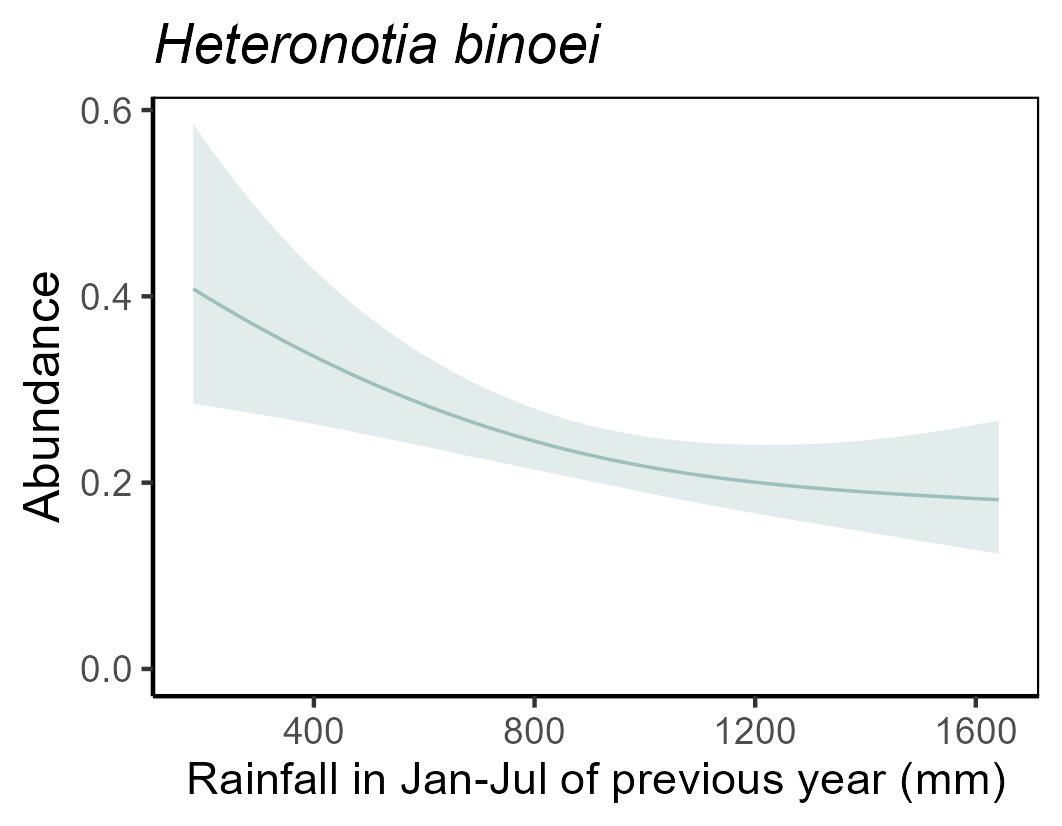

Over the longer term, high rainfall events and floods can have varying effects on populations of different animal species. AWC has conducted an extensive program of Ecohealth monitoring in the Kimberley for 17 years. Comprehensive surveillance surveys are designed to monitor groups of species which are indicative of overall ecosystem health, alongside targeted threatened species surveys. A preliminary analysis of data for four abundant surveillance species shows interesting variation between their responses to the level of rainfall in the preceding year.

Two native rodents, the Western Chestnut Mouse (Pseudomys nanus) and the Pale Field Rat (Rattus tunneyi), show a broadly similar pattern. Their preference seems to be for ‘not too wet, not too dry’, with the probability of trapping them increasing as rainfall increases, but only up to about 1,200 mm, after which capture rates decline. A range of complex ecological factors influence abundance of small mammals in a similar pattern, including food availability, interactions with predators, and reproduction rate.

For a small goanna, the Spiny-tailed Monitor (Varanus acanthurus), the relationship is clear – like other goanna species, they are more likely to be detected after wet years than after dry years, due to the higher availability of prey species.

By contrast, the small and ubiquitous Bynoe’s Gecko (Heteronotia binoei) seems to do better following dry years. One possible explanation is that wetter years provide a boost to the overall number of predators in the ecosystem, increasing pressure on these small nocturnal reptiles.

These species show varied responses to year-to-year variation in rainfall. The long-term datasets AWC produces through our Ecohealth monitoring program are very informative for building a better understanding of how these ecosystems function.

The long timespan of the datasets also makes it possible to discern the inter-annual fluctuations influenced by season, from the substantial population changes which result from AWC’s active conservation management. For example, monitoring indicates that small mammals have shown a sustained increase in abundance over the duration of Ecohealth monitoring at our Kimberley sanctuaries and partnership sites.

Read and download the full issue of Wildlife Matters here.

Help us continue our important conservation work in the Kimberley

Donate Now